There are editorialists in the Agile community who are eager to dismiss practices and frameworks they believe do not align with some orthodox interpretation of the Agile Manifesto. I can appreciate where many of these editorials are coming from because it is no secret that agile transformations fail and fail frequently [1]. The argument is the adoption of fake Agile practices and frameworks that are blatantly unaligned with the Agile Manifesto contributed to the failure. I have to disagree. Poor planning, lack of appreciation for the economic importance of how people work together, and the misuse of practices and frameworks contribute to the failure, and not the practice or framework itself.

It is an ironic paradox these kinds of tribal conversations are even taking place, considering the first value of the agile manifesto is “individual and interactions over processes and tools.” Declaring practices as agile or not is taking a “processes and tools over individuals and interactions” approach to agility. It highlights a belief there is such a thing as an “agile practice” or framework. Let’s be clear: there is no such thing as an “agile” practice or framework. There are recommended ways of working and collaborating that are known to help teams and enterprises start on their agile journey, but you cannot identify a practice or framework as agile or not. If that were the case, then every cargo cult team would be an exemplary agile team.

Let’s be very clear about what agility is: it is the ability to sense and respond faster than the rate of change. In business, it is a time-based strategy for gaining a competitive advantage for economic success. Kent Beck captured the essence of Agile in the title of his XP book “Embrace Change.” A little research quickly reveals agility has long been known as a competitive strategy that existed well before the term was appropriated for the Agility Manifesto [2,3,4,5]. Even 1950s coal miners applied what we would instantly recognize as an agile mindset to dramatically improve output[6]. Our beloved frameworks, Scrum, XP, LeSS, Scrum @ Scale, and SAFe, are proven means for starting a team on their agile journey. But they are not the goal or the only way an enterprise can start on its agile journey.

Case in point: back in 2001, I was collaborating on a book with Alistair Cockburn when, one afternoon, he suddenly phoned me and excitedly told me all about the Snowbird meeting. I just shrugged my shoulders because I have had the good fortune that many of the companies I had worked at had an agile mindset. Our 1980s and 90s software development practices would not be recognizable as Scrum or XP. However, our organizational culture gave us a major competitive advantage and enabled us to operate at a faster tempo than our competitors. In some cases, our fast tempo not only enabled us to respond faster than our competitors to market changes but also enabled us to drive the market changes that frustrated our competitors.

The Agile Manifesto made agility accessible to software developers and inspired many to think about better alternatives to software development than the so-called “Big-M” methodologies that dominated the enterprise landscape. While the Agile Manifesto appropriated the term Agile, it highlighted values that enabled fast sense and respond capabilities for a software team. It was a breath of fresh air.

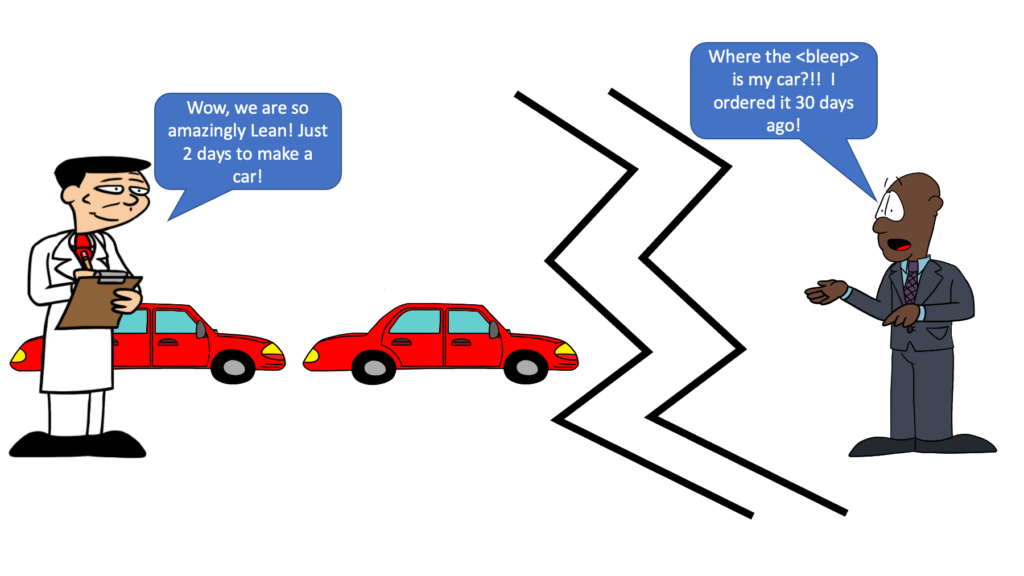

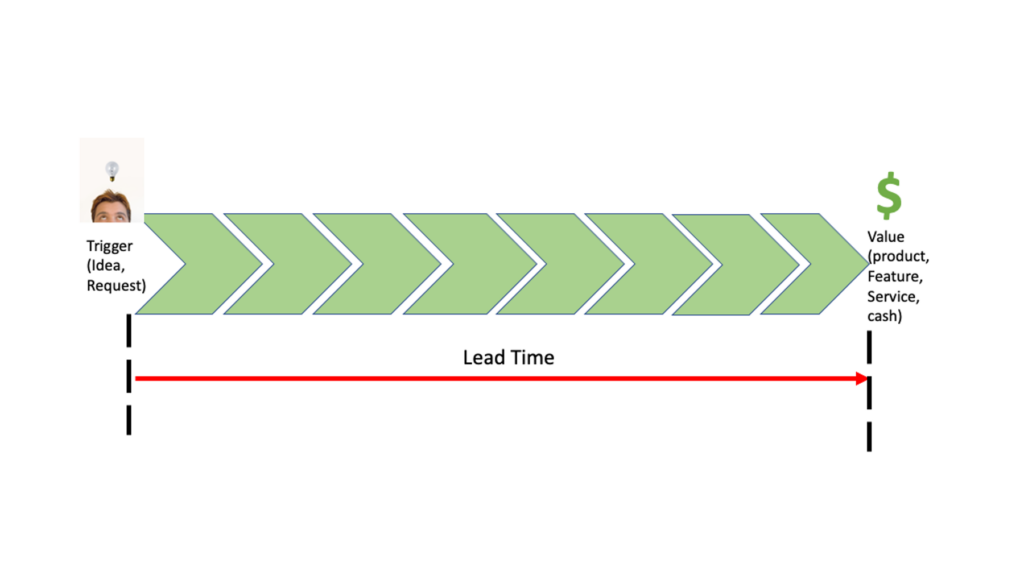

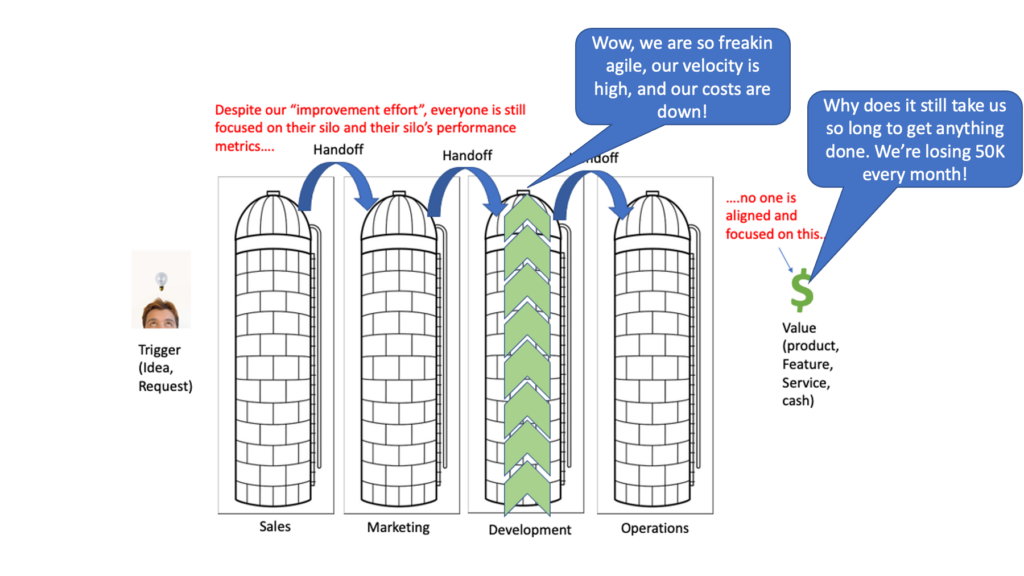

The problem with using the Manifesto as some scripture to bless a practice or framework as agile or demonize it as not, is that it stifles innovation and improvement. Change is the very essence of agile. A “processes and tools” approach to agile makes the goal of agile to be compliance with a specific set of practices rather than fast learning cycles for improving outcomes. As an agile coach, my job is to help my client exploit agility as a strategy for economic success. My job is not to create a textbook example of Scrum, SAFe, DA, or any other framework. Just because a team can write textbook-quality user stories does not make them agile. What I really want to know is, can they predictably get something demonstrable and valuable accomplished within a timebox? What did they learn about both the product and the process? What would it take to shorten the lead time for that learning? Can they quickly learn if they are building the right thing? Can they improve outcomes by experimenting with and changing practices? Now that is Agile as individuals and interactions. I’ve seen too many processes and tools cargo cult organizations where teams go through the framework motions without any real understanding or choice about the practices they pretend to follow.

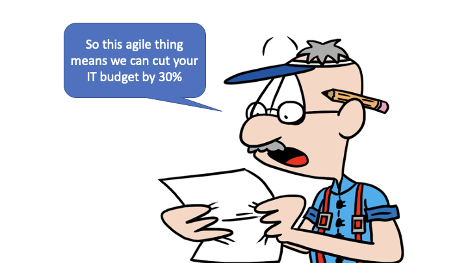

Agile is about learning and using that learning to improve both our product and process. Principled conversations, questioning, and challenging beliefs and practices are good because that is how we learn and advance our profession. After all, a few individuals questioned if our traditional big-M methodologies were the best future for software development and encouraged the emergence of the agile community. However, the puritanical dismissal of practices and frameworks that do not align with an editorialist’s orthodox interpretation of the Agile Manifesto diminishes the Agile community to a collection of competing tribes protecting their territory. Curiosity, learning, and advancement are stifled. Worse, these strong puritanical views are not just pedantic academic arguments. They have led to serious economic consequences for enterprises.

Scrum, LeSS, DA, SAFe, Scrum @ Scale, etc. – We all want the same thing: to help clients deliver value to customers, make improvements along the way, and, of course, make some money by helping them. After all, I have a mortgage to pay and a kid to send to school. I am not a charity. We just have different ways of doing it, but the end goal is the same regardless of the practices or framework chosen. Thus, we have common ground. The reality is our frameworks are sets of integrated practices that start an enterprise on its lean and agile journey. They are not an end to themselves. Dictating which practices “are agile” and which are not takes our attention away from managing outcomes and puts our attention on demanding compliance with a set of blessed practices. And that is not agile.

[1] Davenport, T. H., & Westerman, G. (2018). Why so many high-profile digital transformations fail. Harvard Business Review, 9(4), 15.

[2] Stalk Jr, G., & Hout, T. M. (1990). Competing against time. Research-Technology Management, 33(2), 19-24

[3] Richards, C. (2004). Certain to win: The strategy of John Boyd applied to business. Xlibris Corporation

[4] Freeman, C. (1969). T. Burns and GM Stalker. The Management of Innovation.

[5] Lawrence, P., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration. Boston: Harvard University.

[6] Trist, E. L. (1963). Organizational choice; capabilities of groups at the coal face under changing technologies: the loss, rediscovery and transformation of a work tradition. London: Tavistock